In Lohme, on the isle of Rugen, they left sweets upon the adebarsteine, the stork stones. They did not remember the stories.

Have you ever really listened to the stories meant for children? They are fantastic, sometimes beautiful but they are also warnings, as most tales of youth turn out to be in later days.

If you cry wolf when there is no wolf, eventually you will find yourself locked and luckless in a gaping maw. Should you find a cottage made all of sugar and delight then you should run far and fast away from the witch and her wide, waiting oven. If you place sweets upon the stork stones, the stork will bring a baby to the mother who makes the offering, but it may not be the babe for which she precisely hoped.

The tales are told with smiles and small words, in hopes that they will creep deep into the memory of each growing child and perhaps someday, stay their hand or quiet their shout. There is always a warning. A price to be paid for not heeding the tales.

Children grow to young people and continue to become slightly less young. They court and they dance and eventually they pair off like birds to nest. And then, chicks. Babies. Soft and pale and gurgling. Even the ones that cry all through the night, even they are prized with their tiny fingers, long lashes and chubby limbs. Everyone loves a baby.

Yet, some wives pass year by year with no children, empty knit blankets and cleverly crafted cradles waiting at the hearth-side. The hope and gleam in their eyes dwindles and their patience washes out to sea like the chalk cliffs, pain etched deeper by each wave. Wishes gone unanswered, prayers unfulfilled... but then in the sad oceans of their minds, a half-forgotten memory of a tale surfaces and washes up in a fading dream. The adebarsteine. The offering. The storks.

Desperation turns the warning veneer of old tales transparent. The wives remember a child's tale filled with sweets and storks and babies brought by birds. So silly, but they dare not dismiss even this least likely chance. Storks with their smooth bodies, white feathers and regal bearing. What could be more gentle? The last traces of fear slough off as easily and softly as preened down feathers.

By the pale blush of starlight and the moon glow on luminous cliffs each decides to try this far-fetched plea, but no woman dares to tell another for fear of shame and desperation revealed. Small feet, quiet feet in soft shoes steal into the night, for these things must always happen in the night. Past the sleeping village and beyond the dark oak trees the women go, each in her own time, down to the sea. A rocky shore where pebbles are stacked in tiny cairns, each a game of gravity. There the whisper of waves and the rasp of the spray beckon, each surge of water a tongue licking at the stone.

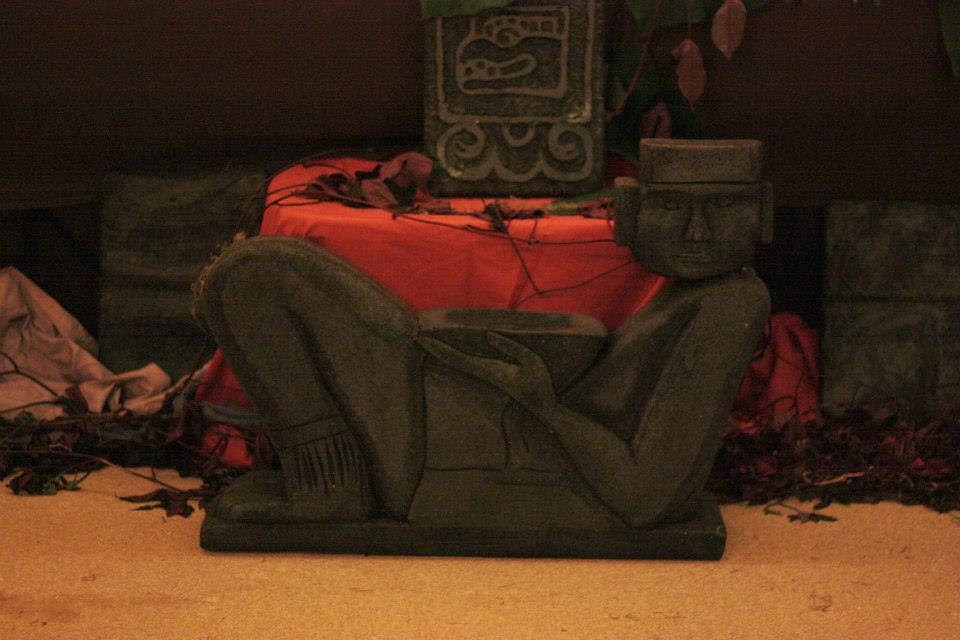

Like altars, the adebarsteine wait.

Each wife filled with a dwindling dream of motherhood shucks off her shoes and hitches up her skirts. It is only ever a short wade to the stork stones. Knee deep into the Baltic, generations of barren wombs and hope-filled hearts make this pilgrimage and then set the bag of sweets upon the rock. Sugar, pure and white and sweet. It seems an easy trade.

A bag of precious confections, cakes, candies and sugared bits left upon the adebarsteine. In return, each woman takes one small pebble, a bit of grit no larger than a grain of sand and swallows it with a mouthful of the Baltic Sea. With eyes squeezed shut and a final, fervent prayer each wife flees the shore to duck back into their cottage, slip quietly back beneath the down coverlet.

The morning after a sacrifice is always the same. Sleepy wives and husbands wake, stretching and picking the rheum from their eyes. A quiet breakfast cooked and bolted down before the door clicks shut behind a husband off to work. It is then, in the quiet of a kitchen, beside the stoking fire, that each wife suddenly and surely becomes aware. Heaviness. A full feeling beyond that of a meal. The knowledge settles in that the offering has been received and something has taken root inside.

The bloom of expectant mother settles over each wife. Her smile quicker, her skin gone rosy as a spring blossom. Over the months they stretch and begin to distend in their middles, growing ungainly as every pregnant woman does. There is an ease to these pregnancies, a lack of sickness and swollen ankles. As their bellies round they press their fingers to their flesh hoping for the feel of a kick, a fist, a baby turning slowly over in a sleepy curl of comfort. Nothing.

Sometimes, late at night they feel a slow grind, as stone against stone or glacier over earth. Nothing smooth, or wet and wriggling. Just a big, firm belly filled where something is becoming. It is usually in these last months that the purposefully forgotten warning of a children's tale begins to seep up through the memory.

A bag of sugar and sweets and a swallowed pebble. A trade of one thing for another. There is a price. There is a charge.

In the village these wives smile through the day, being careful not to look too directly at the storks. Perhaps it was not that there were more of them. Perhaps there had always been so many, and now an awareness had been born. Hope is a funny thing: feathered and flapping faintly in the heart. The last month is always the longest.

And then one night, the wife rises from sleep with a sudden pain, something cracking deep inside. A half dressed husband is shoved out the door to fetch the midwife, leaving a wife in prayer and pacing. There is a sound that begins, faint at first but then louder: a clack and clatter. When the midwife and the husband rush back in, the midwife squints, assessing the wife and looking for the puddle of a babe about to be born and not finding what is expected. And then a sound: a staccato tap. The wife looks into the eyes of the midwife, a look of fear and pleading.

The midwife then stops still, breathes a quiet sigh and shoos the husband from the room where a new life is about to begin. It is for his own good. Go boil water. Go fetch towels. Go cook something so the new mother might have a filling meal after her ordeal. There are things a father should never see. Things a husband should never know.

In these births, few words were exchanged. A grunt of discomfort. A quick instruction of how to sit, or breathe or push. All the while amid the sounds of a husband flailing through a house in a clatter of pans and unfamiliar women's work, still there is a sound growing louder.

Tap. Tap, tap, clack.

A knocking growing insistently and unfailingly louder.

After the groaning and pushing and agony of fear, in a sudden gush of seawater the contents of the womb are expelled and caught by expert hands. An egg, white as sugar with a sheen liked an iced cake sits gleaming in the midwife's hands. The midwife, with an efficiency of practiced motion, walks to the window, throws wide the shutters and places the egg carefully on the sill, a bit of towel tucked around the bottom to keep it from rolling.

At the window the sounds from within the egg quicken and then cracks begin to show, spidering across the smooth and steaming surface of the shell. The midwife sits, hands on knees watching the window, and carefully avoids the eyes of the woman crouching in her bed and dragging the covers over herself, her hands wringing at the sheets.

A crack. A clatter. A flutter and crunch and then a hole appears. A sharp knife of a beak, a smooth white feathered head, a glittering black eye and a sinuous neck unfurl. In moments, a full grown stork stands upon the sill, slowly stretching ink tipped wings and gently preening at a milky white breast. With a last, unblinking stare, the stork turns toward the night and takes wing.

In the silence that follows, a low keening can be heard from the bed. A wife who had hoped against hope to be a mother with her heart broken as surely as an eggshell. With a single whispered command, "Schweig.", the midwife demands quiet, never looking away from the fluttering curtains and the wine dark sky beyond.

Softly. Softly so that the ear must strain and the heart must hope, a distant flapping cuts through the silence. Closer until the individual wing beats can be heard, a pale shape emerges from the night. A stork bearing a heavy burden, looking like a picture from a child's storybook, alights at the sill. A wriggling bundle is lowered down, set upon the towel and the crunching shards of eggshell. In the frozen moment of held breath and staring eyes, a small cry rises. With a last look from an eye black as a jet bead, the stork turns its golden bill back to the night and takes wing.

There are things that women do not say, even in the privacy of the birthing bed. There are glances that carry whole conversations, admonitions of deeds done in desperation. In the candle-flickering shadows, a midwife can pick up a swaddled babe from a window sill and carry it across the room to the shocked arms of a maid turned mother. A German woman, a world-wise midwife, knows how to do these things from the depth of her bones. She can stand straight and unshaken because that is how these things must be. There are no words for a night of old magic: a night of eggs and feathers and foundling babes. Such a midwife knows to place the pale and perfect infant into the arms of a new mother, collect her things and leave the room, pausing only to sweep the shards of eggshell from the windowsill and let them fall into the night.

There is a joy of relief when a deed is done and the hatched plan has come to fruition. A mother reshapes herself to curl around a perfect baby, her fingers exploring toes and ears and fingers almost too tiny to be real. Fathers steal back in to the room and join their new family in bed amid smiling and cooing. The new family begins to shape their world and lives to orbit this new, pale and perfect child. There is happiness and the feel of fear nearly fades away.

Some weeks later, word will travel in from afar. Perhaps from Griefsburg or from Hiddensea. A story of a baby stolen in the night will spread in all directions, a tale of caution whispered among mothers. Close the windows. Latch the shutters. Without vigilance it could be you who wakes to check upon the babe and finds instead a swaddle cloth filled with sea-smoothed pebbles and sometimes a bit of cake, a curl of confection on top.

The story swirls closer and eventually flutters into the house with a new baby. Fear blossoms and guilt flowers in the heart of a young mother and she tries never to meet the eyes of the midwife as they pass in the village. She begins to search for storks, noting each nest and watching for any that seem interested in the chimney tops of houses where pregnant women wait for their babes to be born. She starts to lock the doors at night, propping chairs beneath the knobs and checking each shutter twice.

And then, one night they will awaken to a soft tap at the window. They start awake and leap from their beds running first to check upon their baby, still pale and perfect in the cradle. Another tap, and then more and the mother is filled with fear yet finds herself going to the window and unlatching the shutter to see what is calling.

A stork stands on the sill and drops a bit of cloth from a keenly sharp bill. The napkin flutters open and spills a few crumbs of cake, a few grains of sugar upon the sill. Black eyes look first at the mother, then at the cradle and last turn to the scraps of sugar. With one last, long look into the fear-filled eyes of the trembling woman, the stork turns and drifts into the night with a flash of white and black against a blacker sky.

Understanding blooms. A deal has been made and must continue to be paid. There is no one-time transaction that covers the price of the thing the heart holds most dear. There is a debt. With tear stained cheeks and quaking hands, the mother fills a small sack with sugar, pale and perfect as her babe. Slipping out the door she streaks toward the ocean, feet blurring as she clutches a small sack to her chest.

At the sea, the rocks rise out of the water, no longer deserted. The Adebarsteine are the thrones of tall-legged birds who can fetch a heart's desire from a far cradle. There is a ransom still to pay. Wading out into the salty brine, she places the offering upon an empty altar and then backs slowly away, eyes wary.

In a flash of wings, the storks descend upon the confections, greedy for whatever can be grabbed. Pale beaks flash like knives as the birds squabble for a share. A lone stork leaves the quarrel and takes wing, alighting upon the stone closest to the shaken mother. It lowers a beak and delicately sets down a tiny glinting pebble, a grain not much finer that a bit of sand. Stepping backward, the bird quirks a head to the side, waiting to see if a new pact will be made this night.

The woman shakes her head, still backing away. She runs for the safety of her home, her heart heavy with the weight of a deal that was struck, a deal she did not fully understand. Once home she throws the bolt on the door and drags a chair to brace against the wood. There will be no more sleep this night.

She sits at the table, beside the fading kitchen embers and at once this mother understands two new truths. First, she must begin collecting sugar and hoarding confections against the next time the storks come calling. Second, she tells her heart that one baby is enough.

Kristen Gilpin 4/10/2015